Growth in Africa has outpaced most emerging markets in recent years, but that’s changing fast as a slew of problems beset its leading economies. Here’s what you need to know about sub-Saharan Africa’s big four:

SOUTH AFRICA

The prospects for Africa’s most advanced economy are not looking good. The country is set to grow by just 0.6% this year, according to the International Monetary Fund. It’s one of the slowest growing countries in one of the world’s fastest growing territories.

The rand plummeted 30% last year, and not just because of an emerging market sell-off. Political turmoil has also had a big impact.

Just this month, South African President Jacob Zuma survived impeachment despite the highest court in the land finding him guilty of breaching the constitution over how public money was spent renovating his home. Well known figures from the anti-apartheid struggle are now calling for Zuma to step down.

Chaos in government isn’t helping either. Zuma stunned investors by replacing Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene with a little known politician. The president then backtracked and asked Nene’s predecessor Pravin Gordhan to take the position in order to stop the rand’s freefall.

The rand has steadied this year, rallying by about 7%. It’s been helped by a broader rally in markets driven by rising commodity prices. As a platinum, gold and coal producer, South Africa is sensitive to shifts in the commodity cycle.

But the country is not out of the woods yet. It’s on the brink of a ratings downgrade that would plunge its sovereign debt into junk status.

Still, investors are showing some renewed confidence, buying up $1.86 billion worth of bonds so far in 2016 — the best start to a year since 2010.

NIGERIA

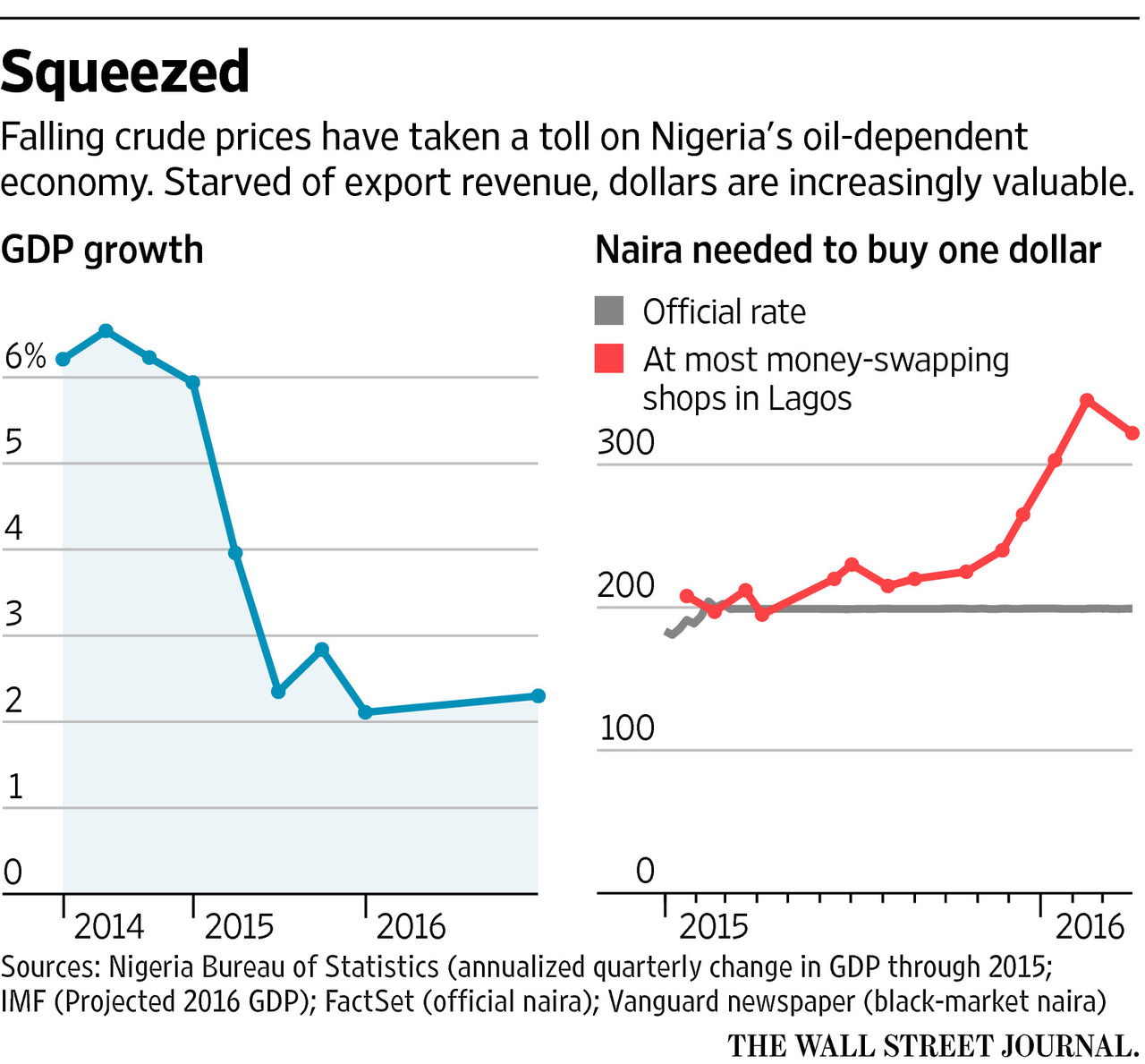

Africa’s largest economy is buckling under the low oil price. Nigeria relies on oil for 70% of government revenue and accounts for 90% of export revenue. That leaves very little room to adjust the country’s budget. For an emerging market that can only mean one thing — slower growth. The West African nation is expected to clock in growth of 2.3%, the lowest rate in 15 years, according to the IMF. Its facing a shortfall of $11 billion in its 2016 budget.

Discussions between Nigeria and the World Bank are continuing on a possible loan or credit facility that would be tied to policy reforms. It has drawn down its currency reserves and implemented capital controls, making access to dollars very difficult. In an economy that relies on imports, the controls have made life difficult for companies and two South African businesses have already pulled out.

Index compiler MSCI is considering removing Nigeria from its frontier market index because the restrictions have made it harder for investors to repatriate money. To make matters worse, the country is facing a fuel crisis. Despite being Africa’s largest oil producer, it has never had enough refining capacity, and the scarcity of dollars is making it harder for importers to bring gas into the country. The war against Al-Qaeda linked terror group Boko Haram, which the government has vowed to eradicate, is placing further strain on the country’s finances.

ANGOLA

What was once one of Africa’s fastest growing economies is now on its knees and asking for help from the IMF. Angola is Africa’s second largest oil producer and relies on oil for 95% of government revenue.

After debuting on the international debt market last year, the country appears unable to meet its budget and debt obligations. It has requested assistance from the IMF in the form of monetary support. Angola is also bound to money-for-oil deals with China. It has used oil as collateral for loans from China, and that is further squeezing state finances. The country is set to grow by 3.5% this year, down from 6.8% in 2013, according to the IMF.

KENYA

Kenya’s economy is more resilient and diversified but there’s trouble brewing in its banking sector. Three banks are being wound down by the central bank. Two of the banks failed last year, and a third was forced into the arms of the lender of last resort this month. A fourth bank is being investigated, and analysts believe consolidation in the industry is inevitable.

The East African nation has 43 banks, most of which have overstated profits and are buckling under the weight of non-performing loans and a big fall in deposits. A dozen banks may end up under central bank control as it tries to clean up the sector. All this is weighing on Kenya’s growth prospects: The IMF has just cut its forecast to 6% for 2016, down from 6.8% previously.