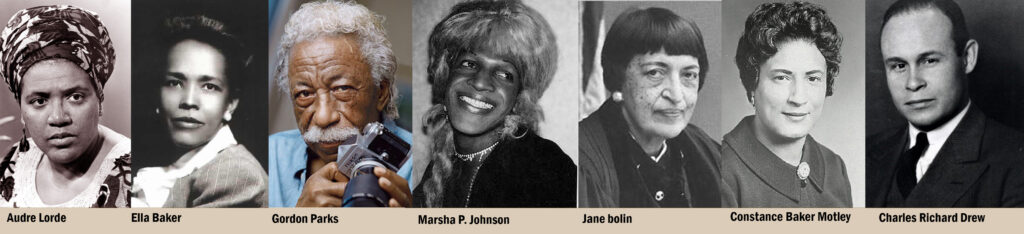

Every Black History Month, we celebrate the same cast of historic figures. These are the civil rights leaders and abolitionists whose faces we see plastered on calendars and postage stamps. This year we are focusing instead on seminal Black figures who don’t often make the history books. They are a few of the unsung heroes.

Culled from the CNN

Audre Lorde:

1934-1992

Her fierce poetry celebrated Black women

Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet. ”That’s how Audre Lorde famously introduced herself.

Her career as a teacher and a writer spanned decades and though she died almost 30 years ago, much of the work she left behind is still cherished and quoted today.

Born to immigrant parents from Grenada, Lorde was raised in Manhattan and published her first poem while still in high school. She served as a librarian in New York public schools before her first book of poetry was published in 1968.

In her work, she called out racism and homophobia and chronicled her own emotional and physical battle with breast cancer. Her writing also humanized Black women in a way that was rare for her time.

As a Black queer woman, Lorde sometimes questioned her place in academic circles dominated by White men. She also battled with feminists she saw as focusing primarily on the experiences of White middle-class women while overlooking women of color.

—Leah Asmelash,

Ella Baker

1903-1986

She risked her life to rally activists in the Deep South

She played a major role in three of the biggest groups of the civil rights movement, but Ella Baker somehow still remains largely unknown outside activist circles.

Baker grew up in North Carolina, where her grandmother’s stories about life under slavery inspired her passion for social justice.

As an adult, she became an organizer within the NAACP and helped co-found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the organization that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. led. She also helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

For her efforts, Baker has been called the “mother of the civil rights movement.”

Baker was best known not as a frontline leader but a mentor to some of the biggest leaders in the movement. She taught volunteers that the movement couldn’t depend solely on charismatic leaders and empowered them to become activists in their own community.

This is the approach that guided SNCC when it embarked on its Freedom Summer voter registration drive in Mississippi in 1964. Baker often risked her life going into small Southern towns to organize.

“The major job,” she once said, “was getting people to understand that they had something within their power that they could use.”

—John Blake

Gordon Parks

1912-2006

His photos chronicled the African American experience

For much of the mid-1900s, it seemed like the world learned about Black America through the eyes of Gordon Parks.

His creative endeavors were astoundingly versatile. Parks performed as a jazz pianist, composed musical scores, wrote 15 books and co-founded Essence magazine.

He adapted his novel “The Learning Tree” into a 1969 film, becoming the first African American to direct a movie for a major studio, and later directed “Shaft,” a hit film that spawned the Blaxploitation genre.

But he reached his artistic peak as a photographer, and his intimate photos of African American life are his most enduring legacy.

—Harmeet Kaur

Marsha P. Johnson

1945-1992

She fought for gay and transgender rights

The late Marsha P. Johnson is celebrated today as a veteran of the Stonewall Inn protests, a pioneering transgender activist and a pivotal figure in the gay liberation movement. Monuments to her life are planned in New York City and her hometown of Elizabeth, New Jersey.

During her lifetime, though, she wasn’t always treated with the same dignity.

When police raided the New York gay bar known as the Stonewall Inn in 1969, Johnson was said to be among the first to resist them. The next year, she marched in the city’s first Gay Pride demonstration.

But Johnson still struggled for full acceptance in the wider gay community, which often excluded transgender people.The term “transgender” wasn’t widely used then, and Johnson referred to herself as gay, a transvestite and a drag queen. She sported flowers in her hair, and told people the P in her name stood for “Pay It No Mind” – a retort she leveled against questions about her gender

Her activism made her a minor celebrity among the artists and outcasts of Lower Manhattan. Andy Warhol took Polaroids of her for a series he did on drag queens.

—Harmeet Kaur,

Jane Bolin

1908-2007

The first Black woman judge in the US.

Jane Bolin made history over and over. She was the first Black woman to graduate from Yale Law School. The first Black woman to join the New York City Bar Association. The nation’s first Black female judge.

The daughter of an influential lawyer, Bolin grew up admiring her father’s leather-bound books while recoiling at photos of lynchings in the NAACP magazine.

Wanting a career in social justice, she graduated from Wellesley and Yale Law School and went into private practice in New York City.

In 1939, New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia appointed her a family court judge. As the first Black female judge in the country, she made national headlines.

For the compassionate Bolin, the job was a good fit. She didn’t wear judicial robes in court to make children feel more at ease and committed herself to seeking equal treatment for all who appeared before her, regardless of their economic or ethnic background.

In an interview after becoming a judge, Bolin said she hoped to show “a broad sympathy for human suffering.”

—Faith Karimi, C

Constance Baker Motley

1921-2005

The first Black woman to argue before the Supreme Court

Constance Baker Motley graduated from her Connecticut high school with honors, but her parents, immigrants from the Caribbean, couldn’t afford to pay for college. So Motley, a youth activist who spoke at community events, made her own good fortune.

A philanthropist heard one of her speeches and was so impressed he paid for her to attend NYU and Columbia Law School. And a brilliant legal career was born.

Motley became the lead trial attorney for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and began arguing desegregation and fair housing cases across the country. The person at the NAACP who hired her? Future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall.

Motley wrote the legal brief for the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education case, which struck down racial segregation in American public schools. Soon she herself was arguing before the Supreme Court – the first Black woman to do so.

Over the years she successfully represented Martin Luther King Jr., Freedom Riders, lunch-counter protesters and the Birmingham Children Marchers. She won nine of the 10 cases that she argued before the high court.

Motley maintained her composure even as some judges turned their backs when she spoke.

“I rejected any notion that my race or sex would bar my success in life,” Motley wrote in her memoir, “Equal Justice Under Law.”

Charles Richard Drew

1904-1950

The father of the blood bank

Anyone who has ever had a blood transfusion owes a debt to Charles Richard Drew, whose immense contributions to the medical field made him one of the most important scientists of the 20th century.

Drew helped develop America’s first large-scale blood banking program in the 1940s, earning him accolades as “the father of the blood bank.”

Drew won a sports scholarship for football and track and field at Amherst College, where a biology professor piqued his interest in medicine. At the time, racial segregation limited the options for medical training for African Americans, leading Drew to attend med school at McGill University in Montréal.

He then became the first Black student to earn a medical doctorate from Columbia University, where his interest in the science of blood transfusions led to groundbreaking work separating plasma from blood. This made it possible to store blood for a week – a huge breakthrough for doctors treating wounded soldiers in World War II.

In 1940, Drew led an effort to transport desperately needed blood and plasma to Great Britain, then under attack by Germany. The program saved countless lives and became a model for a Red Cross pilot program to mass-produce dried plasma.

Ironically, the Red Cross at first excluded Black people from donating blood, making Drew ineligible to participate. That policy was later changed, but the Red Cross segregated blood donations by race, which Drew criticized as “unscientific and insulting.”

Drew also pioneered the bloodmobile — a refrigerated truck that collected, stored and transported blood donations to where they were needed.

Leave a Reply