LAGOS, Nigeria (AP) – Nigeria’s Bring Back Our Girls movement and family members are demanding that the government provide news of the only schoolgirl among 219 kidnapped to escape the clutches of Boko Haram Islamic extremists.

“Even this morning people came to my house asking if I had been able to find out her whereabouts. It’s outrageous! Some people are crying! We don’t understand why the government wants to keep her family away,” Yakubu Nkeki, an uncle of Amina Ali Nkeki, told The Associated Press by telephone on Thursday.

In a statement Wednesday night marking the 800th day of the mass abduction that outraged the world, Bring Back Our Girls also asked what the government is doing to try to rescue the other girls.

Hunters found Ali on May 17, wandering on the fringes of Boko Haram’s Sambisa Forest stronghold with her 4-month-old baby and the father of the child, a Boko Haram fighter who she said helped her escape.

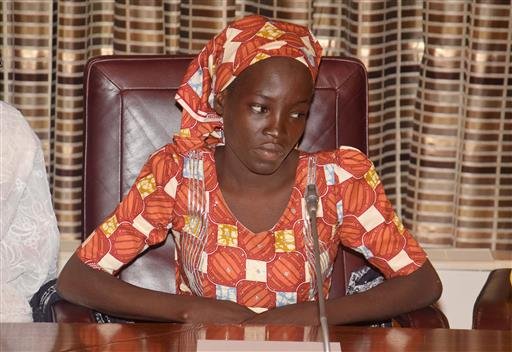

Ali was flown to the capital, Abuja, two days after her escape for a televised meeting at which President Muhammadu Buhari promised her the best care and rehabilitation.The Bring Back Our Girls movement says no one has seen her since, not even leaders of the Chibok community where the girls were kidnapped. It says Ali has said some of the girls have died but most are alive, raising hopes they could still be rescued.

“It is now more than one month since Ms. Ali was rescued and her avowed restoration process by the federal government as pledged by the president began. Having given a reasonable length of time, our movement has a number of concerns regarding Amina Ali as well as the rest of our Chibok girls still in the terrorist enclave,” said the statement signed by the movement’s founders Aisha Yesufu and Oby Ezekwesili.

Government and military officials did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

It had been presumed that Ali would be debriefed by state security agents for information that could lead to a rescue operation, and that she would receive psychosocial care.

Nigeria’s military has freed thousands of Boko Haram captives this year, but none of the girls kidnapped from a remote boarding school in the northeastern town of Chibok in April 2014.

The Associated Press has been unable to establish the whereabouts of some other freed Boko Haram captives taken for alleged debriefing and counseling by the office of the National Security Adviser.

Ali’s uncle said the last time he saw her and her mother, Binta Nkeki, along with baby Safiyah was in the office of the National Security Adviser at the presidential villa on May 19.

“We have had no credible information since, though I am told they are in the hands of the government,” he said.

Bring Back Our Girls also demanded the government prosecute the father of Ali’s child, Mohammed Hayyatu, for abduction and rape. The military has said he appeared to be a Boko Haram commander and was being held for interrogation.

“We are extremely disappointed with the evident lull in rescue actions and lack of any progress report,” the movement said.